Foreign Exchange (FOREX) is the arena where a nation's currency is exchanged for that of another. The foreign exchange market is the largest financial market in the world, with the equivalent of over $1.9 trillion changing hands daily; more than three times the aggregate amount of the US Equity and Treasury markets combined. Unlike other financial markets

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

The Foreign Exchange Market

The primary purpose of the foreign exchange market is to assist international trade and investment, by allowing businesses to convert one currency to another currency. For example, it permits a US business to import European goods and pay Euros, even though the business's income is in US dollars. It also supports speculation, and facilitates the carry trade, in which investors borrow low-yielding currencies and lend (invest in) high-yielding currencies, and which (it has been claimed) may lead to loss of competitiveness in some countries.[2]

In a typical foreign exchange transaction a party purchases a quantity of one currency by paying a quantity of another currency. The modern foreign exchange market started forming during the 1970s when countries gradually switched to floating exchange rates from the previous exchange rate regime, which remained fixed as per the Bretton Woods system.

The foreign exchange market is unique because of its

* huge trading volume, leading to high liquidity

* geographical dispersion

* continuous operation: 24 hours a day except weekends, i.e. trading from 20:15 GMT on Sunday until 22:00 GMT Friday

* the variety of factors that affect exchange rates

* the low margins of relative profit compared with other markets of fixed income

* the use of leverage to enhance profit margins with respect to account size

As such, it has been referred to as the market closest to the ideal of perfect competition, notwithstanding market manipulation by central banks.[citation needed] According to the Bank for International Settlements,[3] average daily turnover in global foreign exchange markets is estimated at $3.98 trillion, as of April 2007. $3.21 Trillion is accounted for in the world's main financial markets.

The $3.21 trillion break-down is as follows:

* $1.005 trillion in spot transactions

* $362 billion in outright forwards

* $1.714 trillion in foreign exchange swaps

* $129 billion estimated gaps in reporting

Dollar shortages and the Marshall Plan

The Bretton Wood arrangements were largely adhered to and ratified by the participating governments. It was expected that national monetary reserves, supplemented with necessary IMF credits, would finance any temporary balance of payments disequilibria. But this did not prove sufficient to get Europe out of its doldrums.

Postwar world capitalism suffered from a huge dollar shortage. The United States was running huge balance of trade surpluses, and the U.S. reserves were immense and growing. It was necessary to reverse this flow. Dollars had to leave the United States and become available for international use. In other words, the United States would have to reverse the natural economic processes and run a balance of payments deficit.

The modest credit facilities of the IMF were clearly insufficient to deal with Western Europe's huge balance of payments deficits. The problem was further aggravated by the reaffirmation by the IMF Board of Governors in the provision in the Bretton Woods Articles of Agreement that the IMF could make loans only for current account deficits and not for capital and reconstruction purposes. Only the United States contribution of $570 million was actually available for IBRD lending. In addition, because the only available market for IBRD bonds was the conservative Wall Street banking market, the IBRD was forced to adopt a conservative lending policy, granting loans only when repayment was assured. Given these problems, by 1947 the IMF and the IBRD themselves were admitting that they could not deal with the international monetary system's economic problems.[8]

The United States set up the European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan) to provide large-scale financial and economic aid for rebuilding Europe largely through grants rather than loans. This included countries belonging to the Soviet bloc, e.g., Poland. In a speech at Harvard University on June 5, 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George Marshall stated:

The breakdown of the business structure of Europe during the war was complete. …Europe's requirements for the next three or four years of foreign food and other essential products… principally from the United States… are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she must have substantial help or face economic, social and political deterioration of a very grave character.

From 1947 until 1958, the U.S. deliberately encouraged an outflow of dollars, and, from 1950 on, the United States ran a balance of payments deficit with the intent of providing liquidity for the international economy. Dollars flowed out through various U.S. aid programs: the Truman Doctrine entailing aid to the pro-U.S. Greek and Turkish regimes, which were struggling to suppress communist revolution, aid to various pro-U.S. regimes in the Third World, and most important, the Marshall Plan. From 1948 to 1954 the United States provided 16 Western European countries $17 billion in grants.

To encourage long-term adjustment, the United States promoted European and Japanese trade competitiveness. Policies for economic controls on the defeated former Axis countries were scrapped. Aid to Europe and Japan was designed to rebuild productivity and export capacity. In the long run it was expected that such European and Japanese recovery would benefit the United States by widening markets for U.S. exports, and providing locations for U.S. capital expansion.

In 1956, the World Bank created the International Finance Corporation and in 1960 it created the International Development Association (IDA). Both have been controversial. Critics of the IDA argue that it was designed to head off a broader based system headed by the United Nations, and that the IDA lends without consideration for the effectiveness of the program. Critics also point out that the pressure to keep developing economies "open" has led to their having difficulties obtaining funds through ordinary channels, and a continual cycle of asset buy up by foreign investors and capital flight by locals. Defenders of the IDA pointed to its ability to make large loans for agricultural programs which aided the "Green Revolution" of the 1960s, and its functioning to stabilize and occasionally subsidize Third World governments, particularly in Latin America.

Bretton Woods, then, created a system of triangular trade: the United States would use the convertible financial system to trade at a tremendous profit with developing nations, expanding industry and acquiring raw materials. It would use this surplus to send dollars to Europe, which would then be used to rebuild their economies, and make the United States the market for their products. This would allow the other industrialized nations to purchase products from the Third World, which reinforced the American role as the guarantor of stability. When this triangle became destabilized, Bretton Woods entered a period of crisis that ultimately led to its collapse.

Bretton Woods system - Designing the IMF

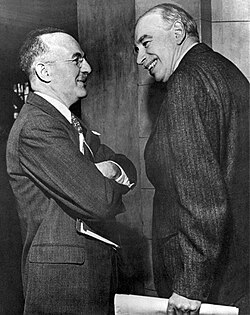

Although attended by 44 nations, discussions at the conference were dominated by two rival plans developed by the United States and Britain. As the chief international economist at the U.S. Treasury in 1942–44, Harry Dexter White drafted the U.S. blueprint for international access to liquidity, which competed with the plan drafted for the British Treasury by Keynes. Overall, White's scheme tended to favor incentives designed to create price stability within the world's economies, while Keynes' wanted a system that encouraged economic growth.

At the time, gaps between the White and Keynes plans seemed enormous. Outlining the difficulty of creating a system that every nation could accept in his speech at the closing plenary session of the Bretton Woods conference on July 22, 1944, Keynes stated:

We, the delegates of this Conference, Mr. President, have been trying to accomplish something very difficult to accomplish.[...] It has been our task to find a common measure, a common standard, a common rule acceptable to each and not irksome to any.

Keynes' proposals would have established a world reserve currency (which he thought might be called "bancor") administered by a central bank vested with the possibility of creating money and with the authority to take actions on a much larger scale (understandable considering deflationary problems in Britain at the time).

In case of balance of payments imbalances, Keynes recommended that both debtors and creditors should change their policies. As outlined by Keynes, countries with payment surpluses should increase their imports from the deficit countries and thereby create a foreign trade equilibrium. Thus, Keynes was sensitive to the problem that placing too much of the burden on the deficit country would be deflationary.

But the United States, as a likely creditor nation, and eager to take on the role of the world's economic powerhouse, balked at Keynes' plan and did not pay serious attention to it. The U.S. contingent was too concerned about inflationary pressures in the postwar economy, and White saw an imbalance as a problem only of the deficit country.

Although compromise was reached on some points, because of the overwhelming economic and military power of the United States, the participants at Bretton Woods largely agreed on White's plan.

Late Bretton Woods System

The design of the Bretton Woods System was that nations could only enforce gold convertibility on the anchor currency—the United States’ dollar. Gold convertibility enforcement was not required, but instead, allowed. Nations could forgo converting dollars to gold, and instead hold dollars. Rather than full convertibility, it provided a fixed price for sales between central banks. However, there was still an open gold market. For the Bretton Woods system to remain workable, it would either have to alter the peg of the dollar to gold, or it would have to maintain the free market price for gold near the $35 per ounce official price. The greater the gap between free market gold prices and central bank gold prices, the greater the temptation to deal with internal economic issues by buying gold at the Bretton Woods price and selling it on the open market.

In 1960 Robert Triffin noticed that holding dollars was more valuable than gold because constant U.S. balance of payments deficits helped to keep the system liquid and fuel economic growth. What would later come to be known as Triffin's Dilemma was predicted when Triffin noted that if the U.S. failed to keep running deficits the system would lose its liquidity, not be able to keep up with the world's economic growth, and, thus, bring the system to a halt. But incurring such payment deficits also meant that, over time, the deficits would erode confidence in the dollar as the reserve currency created instability.[9]

The first effort was the creation of the London Gold Pool on November 1 of 1961 between eight nations. The theory behind the pool was that spikes in the free market price of gold, set by the morning gold fix in London, could be controlled by having a pool of gold to sell on the open market, that would then be recovered when the price of gold dropped. Gold's price spiked in response to events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, and other smaller events, to as high as $40/ounce. The Kennedy administration drafted a radical change of the tax system to spur more production capacity and thus encourage exports. This culminated with the 1963 tax cut program, designed to maintain the $35 peg.

In 1967, there was an attack on the pound and a run on gold in the sterling area, and on November 18, 1967, the British government was forced to devalue the pound.[10] U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson was faced with a brutal choice, either institute protectionist measures, including travel taxes, export subsidies and slashing the budget—or accept the risk of a "run on gold" and the dollar. From Johnson's perspective: "The world supply of gold is insufficient to make the present system workable—particularly as the use of the dollar as a reserve currency is essential to create the required international liquidity to sustain world trade and growth."[11] He believed that the priorities of the United States were correct, and, although there were internal tensions in the Western alliance, that turning away from open trade would be more costly, economically and politically, than it was worth: "Our role of world leadership in a political and military sense is the only reason for our current embarrassment in an economic sense on the one hand and on the other the correction of the economic embarrassment under present monetary systems will result in an untenable position economically for our allies."[citation needed]

While West Germany agreed not to purchase gold from the U.S., and agreed to hold dollars instead, the pressure on both the dollar and the pound sterling continued. In January 1968 Johnson imposed a series of measures designed to end gold outflow, and to increase U.S. exports. This was unsuccessful, however, as in mid-March 1968 a run on gold ensued, the London Gold Pool was dissolved, and a series of meetings attempted to rescue or reform the existing system.[12] But, as long as the U.S. commitments to foreign deployment continued, particularly to Western Europe, there was little that could be done to maintain the gold peg.[citation needed][original research?]

All attempts to maintain the peg collapsed in November 1968, and a new policy program attempted to convert the Bretton Woods system into an enforcement mechanism of floating the gold peg, which would be set by either fiat policy or by a restriction to honor foreign accounts. The collapse of the gold pool and the refusal of the pool members to trade gold with private entities—on March 18, 1968 the Congress of the United States repealed the 25% requirement of gold backing of the dollar[13]—as well as the US pledge to suspend gold sales to governments that trade in the private markets,[14] led to the expansion of the private markets for international gold trade, in which the price of gold rose much higher than the official dollar price.[15] [16] The US gold reserves continued to be depleted due to the actions of some nations, notably France,[16] who continued to build up their gold reserves.

Bretton Woods system - The idea of economic security

Also based on experience of inter-war years, U.S. planners developed a concept of economic security—that a liberal international economic system would enhance the possibilities of postwar peace. One of those who saw such a security link was Cordell Hull, the United States Secretary of State from 1933 to 1944.[Notes 1] Hull believed that the fundamental causes of the two world wars lay in economic discrimination and trade warfare. Specifically, he had in mind the trade and exchange controls (bilateral arrangements) [2] of Nazi Germany and the imperial preference system practiced by Britain, by which members or former members of the British Empire were accorded special trade status, itself provoked by German, French, and American protectionist policies. Hull argued

[U]nhampered trade dovetailed with peace; high tariffs, trade barriers, and unfair economic competition, with war…if we could get a freer flow of trade…freer in the sense of fewer discriminations and obstructions…so that one country would not be deadly jealous of another and the living standards of all countries might rise, thereby eliminating the economic dissatisfaction that breeds war, we might have a reasonable chance of lasting peace.

Great Depression

A high level of agreement among the powerful on the goals and means of international economic management facilitated the decisions reached by the Bretton Woods Conference. Its foundation was based on a shared belief in capitalism. Although the developed countries' governments differed in the type of capitalism they preferred for their national economies (France, for example, preferred greater planning and state intervention, whereas the United States favored relatively limited state intervention), all relied primarily on market mechanisms and on private ownership.

Thus, it is their similarities rather than their differences that appear most striking. All the participating governments at Bretton Woods agreed that the monetary chaos of the interwar period had yielded several valuable lessons.

The experience of the Great Depression was fresh on the minds of public officials. The planners at Bretton Woods hoped to avoid a repeat of the debacle of the 1930s, when intransigent American insistence as a creditor nation on the repayment of Allied war debts, combined with an inclination to isolationism, led to a breakdown of the international financial system and a worldwide economic depression.[1] The "beggar thy neighbor" policies of 1930s governments—using currency devaluations to increase the competitiveness of a country's export products to reduce balance of payments deficits—worsened national deflationary spirals, which resulted in plummeting national incomes, shrinking demand, mass unemployment, and an overall decline in world trade. Trade in the 1930s became largely restricted to currency blocs (groups of nations that use an equivalent currency, such as the "Sterling Area" of the British Empire). These blocs retarded the international flow of capital and foreign investment opportunities. Although this strategy tended to increase government revenues in the short run, it dramatically worsened the situation in the medium and longer run.

Thus, for the international economy, planners at Bretton Woods all favored a regulated system, one that relied on a regulated market with tight controls on the value of currencies. Although they disagreed on the specific implementation of this system, all agreed on the need for tight controls.

Bretton Woods system

Setting up a system of rules, institutions, and procedures to regulate the international monetary system, the planners at Bretton Woods established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), which today is part of the World Bank Group.

Four points in particular stand out. First, negotiators generally agreed that as far as they were concerned, the interwar period had conclusively demonstrated the fundamental disadvantages of unrestrained flexibility of exchange rates. The floating rates of the 1930s were seen as having discouraged trade and investment and to have encouraged destabilizing speculation and competitive depreciations. Yet in an era of more activist economic policy, governments were at the same time reluctant to return to permanently fixed rates on the model of the classical gold standard of the nineteenth century. Policy-makers understandably wished to retain the right to revise currency values on occasion as circumstances warranted. Hence a compromise was sought between the polar alternatives of either freely floating or irrevocably fixed rates - some arrangement that might gain the advantages of both without suffering the disadvantages of either.

Active codes

Code↓ Num↓ E[1]↓ Currency↓ Locations using this currency↓

AED 784 2 United Arab Emirates dirham United Arab Emirates

AFN 971 2 Afghan afghani Afghanistan

ALL 008 2 Albanian lek Albania

AMD 051 2 Armenian dram Armenia

ANG 532 2 Netherlands Antillean guilder Netherlands Antilles

AOA 973 2 Angolan kwanza Angola

ARS 032 2 Argentine peso Argentina

AUD 036 2 Australian dollar Australia, Australian Antarctic Territory, Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Heard and McDonald Islands, Kiribati, Nauru, Norfolk Island, Tuvalu

AWG 533 2 Aruban guilder Aruba

AZN 944 2 Azerbaijani manat Azerbaijan

BAM 977 2 Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark Bosnia and Herzegovina

BBD 052 2 Barbados dollar Barbados

BDT 050 2 Bangladeshi taka Bangladesh

BGN 975 2 Bulgarian lev Bulgaria

BHD 048 3 Bahraini dinar Bahrain

BIF 108 0 Burundian franc Burundi

BMD 060 2 Bermudian dollar (customarily known as Bermuda dollar) Bermuda

BND 096 2 Brunei dollar Brunei, Singapore

BOB 068 2 Boliviano Bolivia

BOV 984 2 Bolivian Mvdol (funds code) Bolivia

BRL 986 2 Brazilian real Brazil

BSD 044 2 Bahamian dollar Bahamas

BTN 064 2 Bhutanese ngultrum Bhutan

BWP 072 2 Botswana pula Botswana

BYR 974 0 Belarusian ruble Belarus

BZD 084 2 Belize dollar Belize

CAD 124 2 Canadian dollar Canada

CDF 976 2 Congolese franc Democratic Republic of Congo

CHE 947 2 WIR Bank (complementary currency) Switzerland

CHF 756 2 Swiss franc Switzerland, Liechtenstein

CHW 948 2 WIR Bank (complementary currency) Switzerland

CLF 990 0 Unidad de Fomento (funds code) Chile

CLP 152 0 Chilean peso Chile

CNY 156 1 Chinese yuan China (Mainland)

COP 170 0 Colombian peso Colombia

COU 970 2 Unidad de Valor Real Colombia

CRC 188 2 Costa Rican colon Costa Rica

CUC 931 2 Cuban convertible peso Cuba

CUP 192 2 Cuban peso Cuba

CVE 132 0 Cape Verde escudo Cape Verde

CZK 203 2 Czech koruna Czech Republic

DJF 262 0 Djiboutian franc Djibouti

DKK 208 2 Danish krone Denmark, Faroe Islands, Greenland

DOP 214 2 Dominican peso Dominican Republic

DZD 012 2 Algerian dinar Algeria

EEK 233 2 Estonian kroon Estonia

EGP 818 2 Egyptian pound Egypt

ERN 232 2 Eritrean nakfa Eritrea

ETB 230 2 Ethiopian birr Ethiopia

EUR 978 2 Euro 16 European Union countries, Andorra, Kosovo, Monaco, Montenegro, San Marino, Vatican City; see eurozone

FJD 242 2 Fiji dollar Fiji

FKP 238 2 Falkland Islands pound Falkland Islands

GBP 826 2 Pound sterling United Kingdom, Crown Dependencies (the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands), certain British Overseas Territories (South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, British Antarctic Territory and British Indian Ocean Territory)

GEL 981 2 Georgian lari Georgia

GHS 936 2 Ghanaian cedi Ghana

GIP 292 2 Gibraltar pound Gibraltar

GMD 270 2 Gambian dalasi Gambia

GNF 324 0 Guinean franc Guinea

GTQ 320 2 Guatemalan quetzal Guatemala

GYD 328 2 Guyanese dollar Guyana

HKD 344 2 Hong Kong dollar Hong Kong Special Administrative Region

HNL 340 2 Honduran lempira Honduras

HRK 191 2 Croatian kuna Croatia

HTG 332 2 Haitian gourde Haiti

HUF 348 2 Hungarian forint Hungary

IDR 360 0 Indonesian rupiah Indonesia

ILS 376 2 Israeli new sheqel Israel

INR 356 2 Indian rupee Bhutan, India, Nepal

IQD 368 0 Iraqi dinar Iraq

IRR 364 0 Iranian rial Iran

ISK 352 0 Icelandic króna Iceland

JMD 388 2 Jamaican dollar Jamaica

JOD 400 3 Jordanian dinar Jordan

JPY 392 0 Japanese yen Japan

KES 404 2 Kenyan shilling Kenya

KGS 417 2 Kyrgyzstani som Kyrgyzstan

KHR 116 0 Cambodian riel Cambodia

KMF 174 0 Comoro franc Comoros

KPW 408 0 North Korean won North Korea

KRW 410 0 South Korean won South Korea

KWD 414 3 Kuwaiti dinar Kuwait

KYD 136 2 Cayman Islands dollar Cayman Islands

KZT 398 2 Kazakhstani tenge Kazakhstan

LAK 418 0 Lao kip Laos

LBP 422 0 Lebanese pound Lebanon

LKR 144 2 Sri Lanka rupee Sri Lanka

LRD 430 2 Liberian dollar Liberia

LSL 426 2 Lesotho loti Lesotho

LTL 440 2 Lithuanian litas Lithuania

LVL 428 2 Latvian lats Latvia

LYD 434 3 Libyan dinar Libya

MAD 504 2 Moroccan dirham Morocco, Western Sahara

MDL 498 2 Moldovan leu Moldova (except Transnistria)

MGA 969 0.7 Malagasy ariary Madagascar

MKD 807 2 Macedonian denar Republic of Macedonia

MMK 104 0 Myanma kyat Myanmar

MNT 496 2 Mongolian tugrik Mongolia

MOP 446 1 Macanese pataca Macau Special Administrative Region

MRO 478 0.7 Mauritanian ouguiya Mauritania

MUR 480 2 Mauritian rupee Mauritius

MVR 462 2 Maldivian rufiyaa Maldives

MWK 454 2 Malawian kwacha Malawi

MXN 484 2 Mexican peso Mexico

MXV 979 2 Mexican Unidad de Inversion (UDI) (funds code) Mexico

MYR 458 2 Malaysian ringgit Malaysia

MZN 943 2 Mozambican metical Mozambique

NAD 516 2 Namibian dollar Namibia

NGN 566 2 Nigerian naira Nigeria

NIO 558 2 Cordoba oro Nicaragua

NOK 578 2 Norwegian krone Norway, Bouvet Island, Queen Maud Land, Peter I Island

NPR 524 2 Nepalese rupee Nepal

NZD 554 2 New Zealand dollar Cook Islands, New Zealand, Niue, Pitcairn, Tokelau

OMR 512 3 Omani rial Oman

PAB 590 2 Panamanian balboa Panama

PEN 604 2 Peruvian nuevo sol Peru

PGK 598 2 Papua New Guinean kina Papua New Guinea

PHP 608 2 Philippine peso Philippines

PKR 586 2 Pakistani rupee Pakistan

PLN 985 2 Polish złoty Poland

PYG 600 0 Paraguayan guaraní Paraguay

QAR 634 2 Qatari rial Qatar

RON 946 2 Romanian new leu Romania

RSD 941 2 Serbian dinar Serbia

RUB 643 2 Russian rouble Russia, Abkhazia, South Ossetia

RWF 646 0 Rwandan franc Rwanda

SAR 682 2 Saudi riyal Saudi Arabia

SBD 090 2 Solomon Islands dollar Solomon Islands

SCR 690 2 Seychelles rupee Seychelles

SDG 938 2 Sudanese pound Sudan

SEK 752 2 Swedish krona/kronor Sweden

SGD 702 2 Singapore dollar Singapore, Brunei

SHP 654 2 Saint Helena pound Saint Helena

SLL 694 0 Sierra Leonean leone Sierra Leone

SOS 706 2 Somali shilling Somalia (except Somaliland)

SRD 968 2 Surinamese dollar Suriname

STD 678 0 São Tomé and Príncipe dobra São Tomé and Príncipe

SYP 760 2 Syrian pound Syria

SZL 748 2 Lilangeni Swaziland

THB 764 2 Thai baht Thailand

TJS 972 2 Tajikistani somoni Tajikistan

TMT 934 2 Turkmenistani manat Turkmenistan

TND 788 3 Tunisian dinar Tunisia

TOP 776 2 Tongan paʻanga Tonga

TRY 949 2 Turkish lira Turkey, Northern Cyprus

TTD 780 2 Trinidad and Tobago dollar Trinidad and Tobago

TWD 901 1 New Taiwan dollar Taiwan and other islands that are under the effective control of the Republic of China (ROC)

TZS 834 2 Tanzanian shilling Tanzania

UAH 980 2 Ukrainian hryvnia Ukraine

UGX 800 0 Ugandan shilling Uganda

USD 840 2 United States dollar American Samoa, British Indian Ocean Territory, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guam, Haiti, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Panama, Puerto Rico, Timor-Leste, Turks and Caicos Islands, United States, Virgin Islands, Bermuda (as well as Bermudian Dollar)

USN 997 2 United States dollar (next day) (funds code) United States

USS 998 2 United States dollar (same day) (funds code) (one source[who?] claims it is no longer used, but it is still on the ISO 4217-MA list) United States

UYU 858 2 Uruguayan peso Uruguay

UZS 860 2 Uzbekistan som Uzbekistan

VEF 937 2 Venezuelan bolívar fuerte Venezuela

VND 704 0 Vietnamese đồng Vietnam

VUV 548 0 Vanuatu vatu Vanuatu

WST 882 2 Samoan tala Samoa

XAF 950 0 CFA franc BEAC Cameroon, Central African Republic, Republic of the Congo, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon

XAG 961 . Silver (one troy ounce)

XAU 959 . Gold (one troy ounce)

XBA 955 . European Composite Unit (EURCO) (bond market unit)

XBB 956 . European Monetary Unit (E.M.U.-6) (bond market unit)

XBC 957 . European Unit of Account 9 (E.U.A.-9) (bond market unit)

XBD 958 . European Unit of Account 17 (E.U.A.-17) (bond market unit)

XCD 951 2 East Caribbean dollar Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Montserrat, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

XDR 960 . Special Drawing Rights International Monetary Fund

XFU Nil . UIC franc (special settlement currency) International Union of Railways

XOF 952 0 CFA Franc BCEAO Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo

XPD 964 . Palladium (one troy ounce)

XPF 953 0 CFP franc French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna

XPT 962 . Platinum (one troy ounce)

XTS 963 . Code reserved for testing purposes

XXX 999 . No currency

YER 886 0 Yemeni rial Yemen

ZAR 710 2 South African rand South Africa

ZMK 894 0 Zambian kwacha Zambia

ZWL 932 2 Zimbabwe dollar Zimbabwe

Currency Codes - Code formation

There is also a three-digit code number assigned to each currency, in the same manner as there is also a three-digit code number assigned to each country as part of ISO 3166. This numeric code is usually the same as the ISO 3166-1 numeric code. For example, USD (United States dollar) has code 840 which is also the numeric code for the US (United States).

The standard also defines the relationship between the major currency unit and any minor currency unit. Often, the minor currency unit has a value that is 1/100 of the major unit, but 1/1000 is also common. Some currencies do not have any minor currency unit at all. In others, the major currency unit has so little value that the minor unit is no longer generally used (e.g. the Japanese sen, 1/100th of a yen). This is indicated in the standard by the currency exponent. For example, USD has exponent 2, while JPY has exponent 0. Mauritania does not use a decimal division of units, setting 1 ouguiya (UM) = 5 khoums, and Madagascar has 1 ariary = 5 iraimbilanja.

ISO 4217 includes codes not only for currencies, but also for precious metals (gold, silver, palladium and platinum; by definition expressed per one troy ounce, as compared to "1 USD") and certain other entities used in international finance, e.g. Special Drawing Rights. There are also special codes allocated for testing purposes (XTS), and to indicate no currency transactions (XXX). These codes all begin with the letter "X". The precious metals use "X" plus the metal's chemical symbol; silver, for example, is XAG. ISO 3166 never assigns country codes beginning with "X", these codes being assigned for privately customized use only (reserved, never for official codes)—for instance, the ISO 3166-based NATO country codes (STANAG 1059, 9th edition) use "X" codes for imaginary exercise countries ranging from XXB for "Brownland" to XXR for "Redland", as well as for major commands such as XXE for SHAPE or XXS for SACLANT. Consequently, ISO 4217 can use "X" codes for non-country-specific currencies without risk of clashing with future country codes.

Supranational currencies, such as the East Caribbean dollar, the CFP franc, the CFA franc BEAC and the CFA franc BCEAO are normally also represented by codes beginning with an "X". The euro is represented by the code EUR (EU is included in the ISO 3166-1 reserved codes list to represent the European Union). The predecessor to the euro, the European Currency Unit (ECU), had the code XEU.

Currency pair

A currency pair is the quotation of the relative value of a currency unit against the unit of another currency in the foreign exchange market. The currency that is used as the reference is called the counter currency or quote currency and the currency that is quoted in relation is called the base currency or transaction currency.

Currency pairs are written by concatenating the ISO currency codes (ISO 4217) of the base currency and the counter currency, separating them with a slash character. Often the slash character is omitted. A widely traded currency pair is the relation of the euro against the US dollar, designated as EUR/USD. The quotation EUR/USD 1.2500 means that one euro is exchanged for 1.2500 US dollars.

The most traded currency pairs in the world are called the Majors. They involve the currencies euro, US dollar, Japanese yen, pound sterling, Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, and the Swiss franc.

The use of high leverage

By offering high leverage, the market maker encourages traders to trade extremely large positions. This increases the trading volume cleared by the market maker and increases his profits, but increases the risk that the trader will receive a margin call. While professional currency dealers (banks, hedge funds) seldom use more than 10:1 leverage, retail clients are generally offered leverage between 50:1 and 200:1[2].

A self-regulating body for the foreign exchange market, the National Futures Association, warns traders in a forex training presentation of the risk in trading currency. “As stated at the beginning of this program, off-exchange foreign currency trading carries a high level of risk and may not be suitable for all customers. The only funds that should ever be used to speculate in foreign currency trading, or any type of highly speculative investment, are funds that represent risk capital; in other words, funds you can afford to lose without affecting your financial situation.“

Not beating the market

Although it is possible for a few experts to successfully arbitrage the market for an unusually large return, this does not mean that a larger number could earn the same returns even given the same tools, techniques and data sources. This is because the arbitrages are essentially drawn from a pool of finite size; although information about how to capture arbitrages is a nonrival good, the arbritrages themselves are a rival good. (To draw an analogy, the total amount of buried treasure on an island is the same, regardless of how many treasure hunters have bought copies of the treasure map.)

Retail traders are - almost by definition - undercapitalized. Thus they are subject to the problem of gambler's ruin. In a fair game (one with no information advantages) between two players that continues until one trader goes bankrupt, the player with the lower amount of capital has a higher probability of going bankrupt first. Since the retail speculator is effectively playing against the market as a whole - which has nearly infinite capital - he will almost certainly go bankrupt.

The retail trader always pays the bid/ask spread which makes his odds of winning less than those of a fair game. Additional costs may include margin interest, or if a spot position is kept open for more than one day the trade may be "resettled" each day, each time costing the full bid/ask spread.

According to the Wall Street Journal (Currency Markets Draw Speculation, Fraud July 26, 2005) "Even people running the trading shops warn clients against trying to time the market. 'If 15% of day traders are profitable,' says Drew Niv, chief executive of FXCM, 'I'd be surprised.' "[16]

Paul Belogour, the Managing Director of a Boston based retail forex trader, was quoted by the Financial Times as saying, "Trading foreign exchange is an excellent way for investors to find out how tough the markets really are. But I say to customers: if this is money you have worked hard for – that you cannot afford to lose – never, never invest in foreign exchange."

Forex scam

"In a typical case, investors may be promised tens of thousands of dollars in profits in just a few weeks or months, with an initial investment of only $5,000. Often, the investor’s money is never actually placed in the market through a legitimate dealer, but simply diverted – stolen – for the personal benefit of the con artists."[5]

In August, 2008 the CFTC set up a special task force to deal with growing foreign exchange fraud.”[6] In January 2010, the CFTC proposed new rules limiting leverage to 10 to 1, based on " a number of improper practices" in the retail foreign exchange market, "among them solicitation fraud, a lack of transparency in the pricing and execution of transactions, unresponsiveness to customer complaints, and the targeting of unsophisticated, elderly, low net worth and other vulnerable individuals."[7]

The forex market is a zero-sum game,[8] meaning that whatever one trader gains, another loses, except that brokerage commissions and other transaction costs are subtracted from the results of all traders, technically making forex a "negative-sum" game.

These scams might include churning of customer accounts for the purpose of generating commissions, selling software that is supposed to guide the customer to large profits,[9] improperly managed "managed accounts",[10] false advertising,[11] Ponzi schemes and outright fraud.[4][12] It also refers to any retail forex broker who indicates that trading foreign exchange is a low risk, high profit investment.[13]

The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which loosely regulates the foreign exchange market in the United States, has noted an increase in the amount of unscrupulous activity in the non-bank foreign exchange industry.[14]

An official of the National Futures Association was quoted as saying, "Retail forex trading has increased dramatically over the past few years. Unfortunately, the amount of forex fraud has also increased dramatically."[15] Between 2001 and 2006 the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission has prosecuted more than 80 cases involving the defrauding of more than 23,000 customers who lost $350 million. From 2001 to 2007, about 26,000 people lost $460 million in forex frauds.[1] CNN quoted Godfried De Vidts, President of the Financial Markets Association, a European body, as saying, "Banks have a duty to protect their customers and they should make sure customers understand what they are doing. Now if people go online, on non-bank portals, how is this control being done?"

Foreign exchange controls

Foreign exchange controls are various forms of controls imposed by a government on the purchase/sale of foreign currencies by residents or on the purchase/sale of local currency by nonresidents.

Common foreign exchange controls include:

- Banning the use of foreign currency within the country

- Banning locals from possessing foreign currency

- Restricting currency exchange to government-approved exchangers

- Fixed exchange rates

- Restrictions on the amount of currency that may be imported or exported

Countries with foreign exchange controls are also known as "Article 14 countries," after the provision in the International Monetary Fund agreement allowing exchange controls for transitional economies. Such controls used to be common in most countries, particularly poorer ones, until the 1990s when free trade and globalization started a trend towards economic liberalization. Today, countries which still impose exchange controls are the exception rather than the rule.

Risk Aversion in Forex

Risk Aversion in the Forex is a kind of trading behavior exhibited by the foreign exchange market when a potentially adverse event happens which may affect market conditions.

This behavior is caused when risk averse traders liquidate their positions in risky assets and shift the funds to less risky assets due to uncertainty.[23]

In the context of the forex market, traders liquidate their positions in various currencies to take up positions in safe haven currencies, such as the US Dollar.[24]

Sometimes the choice of a safe haven currency is more of a choice based on prevailing sentiments rather than one of economic statistics.

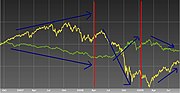

An example would be the Financial Crisis of 2008. The value of equities across world fell while the US Dollar strengthened.( See Fig.1 ) This happened despite the strong focus of the crisis in the USA.[25]

Speculation

Controversy about currency speculators and their effect on currency devaluations and national economies recurs regularly. Nevertheless, economists including Milton Friedman have argued that speculators ultimately are a stabilizing influence on the market and perform the important function of providing a market for hedgers and transferring risk from those people who don't wish to bear it, to those who do.[18] Other economists such as Joseph Stiglitz consider this argument to be based more on politics and a free market philosophy than on economics.[19]

Large hedge funds and other well capitalized "position traders" are the main professional speculators. According to some economists, individual traders could act as "noise traders" and have a more destabilizing role than larger and better informed actors [20].

Currency speculation is considered a highly suspect activity in many countries. [where?] While investment in traditional financial instruments like bonds or stocks often is considered to contribute positively to economic growth by providing capital, currency speculation does not; according to this view, it is simply gambling that often interferes with economic policy. For example, in 1992, currency speculation forced the Central Bank of Sweden to raise interest rates for a few days to 500% per annum, and later to devalue the krona.[21] Former Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad is one well known proponent of this view. He blamed the devaluation of the Malaysian ringgit in 1997 on George Soros and other speculators.

Gregory J. Millman reports on an opposing view, comparing speculators to "vigilantes" who simply help "enforce" international agreements and anticipate the effects of basic economic "laws" in order to profit.[22]

In this view, countries may develop unsustainable financial bubbles or otherwise mishandle their national economies, and foreign exchange speculators made the inevitable collapse happen sooner. A relatively quick collapse might even be preferable to continued economic mishandling, followed by an eventual, larger, collapse. Mahathir Mohamad and other critics of speculation are viewed as trying to deflect the blame from themselves for having caused the unsustainable economic conditions.

Market psychology

Market psychology and trader perceptions influence the foreign exchange market in a variety of ways:

- Flights to quality: Unsettling international events can lead to a "flight to quality," with investors seeking a "safe haven." There will be a greater demand, thus a higher price, for currencies perceived as stronger over their relatively weaker counterparts. The U.S. dollar, Swiss franc and gold have been traditional safe havens during times of political or economic uncertainty.[14]

- Long-term trends: Currency markets often move in visible long-term trends. Although currencies do not have an annual growing season like physical commodities, business cycles do make themselves felt. Cycle analysis looks at longer-term price trends that may rise from economic or political trends.[15]

- "Buy the rumor, sell the fact": This market truism can apply to many currency situations. It is the tendency for the price of a currency to reflect the impact of a particular action before it occurs and, when the anticipated event comes to pass, react in exactly the opposite direction. This may also be referred to as a market being "oversold" or "overbought".[16] To buy the rumor or sell the fact can also be an example of the cognitive bias known as anchoring, when investors focus too much on the relevance of outside events to currency prices.

- Economic numbers: While economic numbers can certainly reflect economic policy, some reports and numbers take on a talisman-like effect: the number itself becomes important to market psychology and may have an immediate impact on short-term market moves. "What to watch" can change over time. In recent years, for example, money supply, employment, trade balance figures and inflation numbers have all taken turns in the spotlight.

- Technical trading considerations: As in other markets, the accumulated price movements in a currency pair such as EUR/USD can form apparent patterns that traders may attempt to use. Many traders study price charts in order to identify such patterns.

Political conditions

Internal, regional, and international political conditions and events can have a profound effect on currency markets.

All exchange rates are susceptible to political instability and anticipations about the new ruling party. Political upheaval and instability can have a negative impact on a nation's economy. For example, destabilization of coalition governments in Pakistan and Thailand can negatively affect the value of their currencies. Similarly, in a country experiencing financial difficulties, the rise of a political faction that is perceived to be fiscally responsible can have the opposite effect. Also, events in one country in a region may spur positive/negative interest in a neighboring country and, in the process, affect its currency.

Economic factors

(a)economic policy, disseminated by government agencies and central banks,

(b)economic conditions, generally revealed through economic reports, and other economic indicators.

* Economic policy comprises government fiscal policy (budget/spending practices) and monetary policy (the means by which a government's central bank influences the supply and "cost" of money, which is reflected by the level of interest rates).

* Government budget deficits or surpluses: The market usually reacts negatively to widening government budget deficits, and positively to narrowing budget deficits. The impact is reflected in the value of a country's currency.

* Balance of trade levels and trends: The trade flow between countries illustrates the demand for goods and services, which in turn indicates demand for a country's currency to conduct trade. Surpluses and deficits in trade of goods and services reflect the competitiveness of a nation's economy. For example, trade deficits may have a negative impact on a nation's currency.

* Inflation levels and trends: Typically a currency will lose value if there is a high level of inflation in the country or if inflation levels are perceived to be rising. This is because inflation erodes purchasing power, thus demand, for that particular currency. However, a currency may sometimes strengthen when inflation rises because of expectations that the central bank will raise short-term interest rates to combat rising inflation.

* Economic growth and health: Reports such as GDP, employment levels, retail sales, capacity utilization and others, detail the levels of a country's economic growth and health. Generally, the more healthy and robust a country's economy, the better its currency will perform, and the more demand for it there will be.

* Productivity of an economy: Increasing productivity in an economy should positively influence the value of its currency. Its effects are more prominent if the increase is in the traded sector

Determinants of FX rates

The following theories explain the fluctuations in FX rates in a floating exchange rate regime (In a fixed exchange rate regime, FX rates are decided by its government):

- (a) International parity conditions: Relative Purchasing Power Parity, interest rate parity, Domestic Fisher effect, International Fisher effect. Though to some extent the above theories provide logical explanation for the fluctuations in exchange rates, yet these theories falter as they are based on challengeable assumptions [e.g., free flow of goods, services and capital] which seldom hold true in the real world.

- (b) Balance of payments model (see exchange rate): This model, however, focuses largely on tradable goods and services, ignoring the increasing role of global capital flows. It failed to provide any explanation for continuous appreciation of dollar during 1980s and most part of 1990s in face of soaring US current account deficit.

- (c) Asset market model (see exchange rate): views currencies as an important asset class for constructing investment portfolios. Assets prices are influenced mostly by people’s willingness to hold the existing quantities of assets, which in turn depends on their expectations on the future worth of these assets. The asset market model of exchange rate determination states that “the exchange rate between two currencies represents the price that just balances the relative supplies of, and demand for, assets denominated in those currencies.”

None of the models developed so far succeed to explain FX rates levels and volatility in the longer time frames. For shorter time frames (less than a few days) algorithm can be devised to predict prices. Large and small institutions and professional individual traders have made consistent profits from it. It is understood from above models that many macroeconomic factors affect the exchange rates and in the end currency prices are a result of dual forces of demand and supply. The world's currency markets can be viewed as a huge melting pot: in a large and ever-changing mix of current events, supply and demand factors are constantly shifting, and the price of one currency in relation to another shifts accordingly. No other market encompasses (and distills) as much of what is going on in the world at any given time as foreign exchange.

Supply and demand for any given currency, and thus its value, are not influenced by any single element, but rather by several. These elements generally fall into three categories: economic factors, political conditions and market psychology.

Monday, June 21, 2010

Trading characteristics

| Rank | Currency | ISO 4217 code (Symbol) | % daily share (April 2007) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | USD ($) | 86.3% | |

| 2 | EUR (€) | 37.0% | |

| 3 | JPY (¥) | 17.0% | |

| 4 | GBP (£) | 15.0% | |

| 5 | CHF (Fr) | 6.8% | |

| 6 | AUD ($) | 6.7% | |

| 7 | CAD ($) | 4.2% | |

| 8-9 | SEK (kr) | 2.8% | |

| 8-9 | HKD ($) | 2.8% | |

| 10 | NOK (kr) | 2.2% | |

| 11 | NZD ($) | 1.9% | |

| 12 | MXN ($) | 1.3% | |

| 13 | SGD ($) | 1.2% | |

| 14 | KRW (₩) | 1.1% | |

| Other | 14.5% | ||

| Total | 200% | ||

There is no unified or centrally cleared market for the majority of FX trades, and there is very little cross-border regulation. Due to the over-the-counter (OTC) nature of currency markets, there are rather a number of interconnected marketplaces, where different currencies instruments are traded. This implies that there is not a single exchange rate but rather a number of different rates (prices), depending on what bank or market maker is trading, and where it is. In practice the rates are often very close, otherwise they could be exploited by arbitrageurs instantaneously. Due to London's dominance in the market, a particular currency's quoted price is usually the London market price. A joint venture of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and Reuters, called Fxmarketspace opened in 2007 and aspired but failed to the role of a central market clearing mechanism.[citation needed]

The main trading center is London, but New York, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Singapore are all important centers as well. Banks throughout the world participate. Currency trading happens continuously throughout the day; as the Asian trading session ends, the European session begins, followed by the North American session and then back to the Asian session, excluding weekends.

Fluctuations in exchange rates are usually caused by actual monetary flows as well as by expectations of changes in monetary flows caused by changes in gross domestic product (GDP) growth, inflation (purchasing power parity theory), interest rates (interest rate parity, Domestic Fisher effect, International Fisher effect), budget and trade deficits or surpluses, large cross-border M&A deals and other macroeconomic conditions. Major news is released publicly, often on scheduled dates, so many people have access to the same news at the same time. However, the large banks have an important advantage; they can see their customers' order flow.

Currencies are traded against one another. Each currency pair thus constitutes an individual trading product and is traditionally noted XXXYYY or XXX/YYY, where XXX and YYY are the ISO 4217 international three-letter code of the currencies involved. The first currency (XXX) is the base currency that is quoted relative to the second currency (YYY), called the counter currency (or quote currency). For instance, the quotation EURUSD (EUR/USD) 1.5465 is the price of the euro expressed in US dollars, meaning 1 euro = 1.5465 dollars. Historically, the base currency was the stronger currency at the creation of the pair. However, when the euro was created, the European Central Bank mandated that it always be the base currency in any pairing.

The factors affecting XXX will affect both XXXYYY and XXXZZZ. This causes positive currency correlation between XXXYYY and XXXZZZ.

On the spot market, according to the BIS study, the most heavily traded products were:

- EURUSD: 27%

- USDJPY: 13%

- GBPUSD (also called cable): 12%

and the US currency was involved in 86.3% of transactions, followed by the euro (37.0%), the yen (17.0%), and sterling (15.0%) (see table). Volume percentages for all individual currencies should add up to 200%, as each transaction involves two currencies.

Trading in the euro has grown considerably since the currency's creation in January 1999, and how long the foreign exchange market will remain dollar-centered is open to debate. Until recently, trading the euro versus a non-European currency ZZZ would have usually involved two trades: EURUSD and USDZZZ. The exception to this is EURJPY, which is an established traded currency pair in the interbank spot market. As the dollar's value has eroded during 2008, interest in using the euro as reference currency for prices in commodities (such as oil), as well as a larger component of foreign reserves by banks, has increased dramatically. Transactions in the currencies of commodity-producing countries, such as AUD, NZD, CAD, have also increased.

Non-bank foreign exchange companies

Non-bank foreign exchange companies offer currency exchange and international payments to private individuals and companies. These are also known as foreign exchange brokers but are distinct in that they do not offer speculative trading but currency exchange with payments. I.e., there is usually a physical delivery of currency to a bank account. Send Money Home offer an in-depth comparison into the services offered by all the major non-bank foreign exchange companies.

It is estimated that in the UK, 14% of currency transfers/payments[12] are made via Foreign Exchange Companies.[13] These companies' selling point is usually that they will offer better exchange rates or cheaper payments than the customer's bank. These companies differ from Money Transfer/Remittance Companies in that they generally offer higher-value services.

Retail foreign exchange brokers

There are two main types of retail FX brokers offering the opportunity for speculative currency trading: brokers and dealers or market makers. Brokers serve as an agent of the customer in the broader FX market, by seeking the best price in the market for a retail order and dealing on behalf of the retail customer. They charge a commission or mark-up in addition to the price obtained in the market. Dealers or market makers, by contrast, typically act as principal in the transaction versus the retail customer, and quote a price they are willing to deal at—the customer has the choice whether or not to trade at that price.

In assessing the suitability of an FX trading service, the customer should consider the ramifications of whether the service provider is acting as principal or agent. When the service provider acts as agent, the customer is generally assured of a known cost above the best inter-dealer FX rate. When the service provider acts as principal, no commission is paid, but the price offered may not be the best available in the market—since the service provider is taking the other side of the transaction, a conflict of interest may occur.

Investment management firms

Investment management firms (who typically manage large accounts on behalf of customers such as pension funds and endowments) use the foreign exchange market to facilitate transactions in foreign securities. For example, an investment manager bearing an international equity portfolio needs to purchase and sell several pairs of foreign currencies to pay for foreign securities purchases.

Some investment management firms also have more speculative specialist currency overlay operations, which manage clients' currency exposures with the aim of generating profits as well as limiting risk. Whilst the number of this type of specialist firms is quite small, many have a large value of assets under management (AUM), and hence can generate large trades.

Hedge funds as speculators

About 70% to 90% [citation needed] of the foreign exchange transactions are speculative. In other words, the person or institution that bought or sold the currency has no plan to actually take delivery of the currency in the end; rather, they were solely speculating on the movement of that particular currency. Hedge funds have gained a reputation for aggressive currency speculation since 1996. They control billions of dollars of equity and may borrow billions more, and thus may overwhelm intervention by central banks to support almost any currency, if the economic fundamentals are in the hedge funds' favor.

Central banks

The mere expectation or rumor of central bank intervention might be enough to stabilize a currency, but aggressive intervention might be used several times each year in countries with a dirty float currency regime. Central banks do not always achieve their objectives. The combined resources of the market can easily overwhelm any central bank.[9] Several scenarios of this nature were seen in the 1992–93 ERM collapse, and in more recent times in Southeast Asia.

Commercial companies

Nevertheless, trade flows are an important factor in the long-term direction of a currency's exchange rate. Some multinational companies can have an unpredictable impact when very large positions are covered due to exposures that are not widely known by other market participants.

Banks

The interbank market caters for both the majority of commercial turnover and large amounts of speculative trading every day. A large bank may trade billions of dollars daily. Some of this trading is undertaken on behalf of customers, but much is conducted by proprietary desks, trading for the bank's own account. Until recently, foreign exchange brokers did large amounts of business, facilitating interbank trading and matching anonymous counterparts for small fees.

Today, however, much of this business has moved on to more efficient electronic systems. The broker squawk box lets traders listen in on ongoing interbank trading and is heard in most trading rooms, but turnover is noticeably smaller than just a few years ago.

Market participants

Market size and liquidity

The foreign exchange market is the largest and most liquid financial market in the world. Traders include large banks, central banks, currency speculators, corporations, governments, and other financial institutions. The average daily volume in the global foreign exchange and related markets is continuously growing. Daily turnover was reported to be over US$3.2 trillion in April 2007 by the Bank for International Settlements. [3] Since then, the market has continued to grow. According to Euromoney's annual FX Poll, volumes grew a further 41% between 2007 and 2008.[4]

Of the $3.98 trillion daily global turnover, trading in London accounted for around $1.36 trillion, or 34.1% of the total, making London by far the global center for foreign exchange. In second and third places respectively, trading in New York City accounted for 16.6%, and Tokyo accounted for 6.0%.[5] In addition to "traditional" turnover, $2.1 trillion was traded in derivatives.

Exchange-traded FX futures contracts were introduced in 1972 at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and are actively traded relative to most other futures contracts.

Several other developed countries also permit the trading of FX derivative products (like currency futures and options on currency futures) on their exchanges. All these developed countries already have fully convertible capital accounts. Most emerging countries do not permit FX derivative products on their exchanges in view of prevalent controls on the capital accounts. However, a few select emerging countries (e.g., Korea, South Africa, India—[1]; [2]) have already successfully experimented with the currency futures exchanges, despite having some controls on the capital account.

FX futures volume has grown rapidly in recent years, and accounts for about 7% of the total foreign exchange market volume, according to The Wall Street Journal Europe (5/5/06, p. 20).

| Rank | Name | Market Share |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.06% | |

| 2 | 11.30% | |

| 3 | 11.08% | |

| 4 | 7.69% | |

| 5 | 6.50% | |

| 6 | 6.35% | |

| 7 | 4.55% | |

| 8 | 4.44% | |

| 9 | 4.28% | |

| 10 | 2.91% |

Foreign exchange trading increased by 38% between April 2005 and April 2006 and has more than doubled since 2001. This is largely due to the growing importance of foreign exchange as an asset class and an increase in fund management assets, particularly of hedge funds and pension funds. The diverse selection of execution venues have made it easier for retail traders to trade in the foreign exchange market. In 2006, retail traders constituted over 2% of the whole FX market volumes with an average daily trade volume of over US$50-60 billion (see retail trading platforms).[7]

Because foreign exchange is an OTC market where brokers/dealers negotiate directly with one another, there is no central exchange or clearing house. The biggest geographic trading centre is the UK, primarily London, which according to IFSL estimates has increased its share of global turnover in traditional transactions from 31.3% in April 2004 to 34.1% in April 2007. Due to London's dominance in the market, a particular currency's quoted price is usually the London market price. For instance, when the IMF calculates the value of its SDRs every day, they use the London market prices at noon that day.

The ten most active traders account for 77% of trading volume, according to the 2010 Euromoney FX survey.[8] These large international banks continually provide the market with both bid (buy) and ask (sell) prices. The bid/ask spread is the difference between the price at which a bank or market maker will sell ("ask", or "offer") and the price at which a market taker will buy ("bid") from a wholesale or retail customer. The customer will buy from the market-maker at the higher "ask" price, and will sell at the lower "bid" price, thus giving up the "spread" as the cost of completing the trade. This spread is minimal for actively traded pairs of currencies, usually 0–3 pips. For example, the bid/ask quote of EURUSD might be 1.2200/1.2203 on a wholesale broker. Minimum trading size for most deals is usually 1,000,000 units of base currency, which is a standard "lot".

These spreads might not apply to retail customers at banks, which will routinely mark up the difference to say 1.2100/1.2300 for transfers, or say 1.2000/1.2400 for banknotes or travelers' checks. Spot prices at market makers vary, but on EURUSD are usually no more than 3 pips wide (i.e., 0.0003). Competition is greatly increased with larger transactions, and pip spreads shrink on the major pairs to as little as 1 to 2 pips.